Dr. Aamir Jafarey's mini-urban forest

I just saw a butterfly. It was black and it was beautiful. And it was in my mini-urban forest. It was almost as amazing as seeing my avocado plant take root and begin to thrive, and a baby guava appear unexpectedly. But this would all have happened anyway. Only Covid happened, and the lockdown, these otherwise nonevents became, for me, moments to marvel and reflect.

Covid has of course been devastating. The death, the disease, the disruption. The world will take a long time to regain some semblance of normalcy. And while some things will never be the same again, the world will ultimately limp back to a routine, perhaps accepting a new normal. In a country where over 400,000 babies die yearly, and not a dent is made on our collective conscience, what’s a few hundred more deaths a year, from Covid and other infections? Chronicity is a great normalizer. While you vow to fight it, you also tend to learn to live with it.

On the other hand, acuteness-ity is generally unwelcome. It necessitates adapting to unwelcome change.

#WFH was one such change. While still in denial, we too moved our work lives to our homes, not quite knowing what that would actually mean. Office means a certain discipline, a routine, a formality to our work, a time to begin the day and a time to end it. Leaving “on the stroke of 5”, signified an end. And at least for some, a new beginning. Perhaps, at least on some days, the best of the day lay beyond 5 pm.

Not that I don’t love my office. My office is me, totally me. I love what it represents, what I have been able to accomplish there. It is the space where I have dreamt wild dreams, convinced others quite masterfully of joint ownership, and seen fruition. Yes, I take full advantage of my devious ways.

I am a morning person, people tell me. My post-3 pm synaptic delays are legendary. I have to fight to keep awake, focused and coherent during meetings which at office typically begin at the stroke of 3, our official prime time. And it's generally downhill then on. Five pm therefore signified an escape for me, an opportunity to nap on my way home on my Uber ride.

With #WFH, suddenly there was no 5 pm. There was work, lots of it, but no timings. Work, Post-Covid, expanded to envelop every waking hour. And yet, it was not tiring or burdensome. I was quite at home working from home.

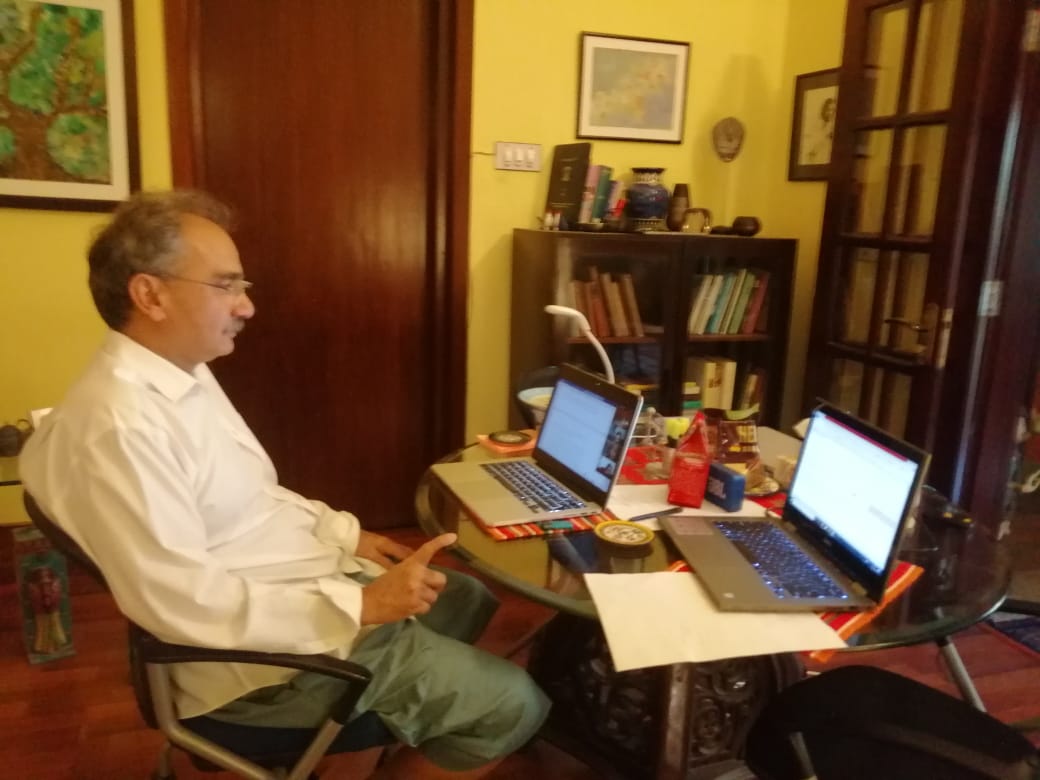

#WFH - Dr. Aamir multi-tasking at home

The family room sheeshay wali gol maiz (glass table) became my office desk, my daughter’s hand-me-down 5 year old MacBook my office computer, and Zoom became our meeting platform.

The day would start at 8 am with me in a fresh set of PJs. But work would go on way past midnight, with 30 minute breaks for things I never imagined I would be doing. Like going to the corner cluster of stores to pick up milk and bhindi (okra), and buns to make my daughter my trademark sumptuous burgers.

But it's not the bhindi runs that have kept me recharged. It's siesta. While I have always believed in the power of the snooze, these 5 weeks have provided me an opportunity to test my hypothesis. A 20 minute afternoon power nap, and I’m reset with all synapses firing synchronously for the next several hours!

And somehow, my senses are sharper, #WFH.

Sitting in the family room, while working on the guidelines, or a research proposal review for the National Bioethics Committee, or making sense of garbled DRAP projects, I would become aware of the birds chirping in the backyard. Were the birds also under lockdown, unable to fly away, hence the noisy “conference of the birds” on the mango tree outside? Or had I just become more observant?

This has been the time of discoveries. Like the amount of eggs and dabal roti (bread) that is consumed in my house, and how frequently detergents run out. Who eats this amount of makhan (butter) anyway?

Zoom, like work, also has the capability of transcending time. Since no one actually had to “go” anywhere, there was generally no real compulsion to stop. Having already mastered the art of half dressing for video conferencing, I quickly learnt how to discreetly disappear to flip the chicken in the oven while my colleague rambled on with her comments; one can’t have the roast overdone on one side just because of a meeting, can one?

And I perfected the correct combo for a stellar dum ka kabab, marinated overnight with hara papita (raw papaya) from my urban forest mixed in the home ground masala.

Where is the sil batta (grinding stone), I inquired one day. What sil batta? said my wife, raising her head momentarily from her computer, sitting in her dining room office. Who uses a sil batta these days, and why on earth do you need it - to fine grind a research review?

So it was the bijli ka (electric) grinder in the end.

But those were killer kababs, I can tell you that! Not bad for a first attempt! Without really knowing, I had slid very comfortably into the role of a homemaker, much to the relief of my teacher-administrator wife, mastering the art of conducting 5 hour long online classes, using 3 computers!

Whether it was the publications, the feeling of being able to contribute nationally with the research reviews, pushing the guidelines for resource allocation through again to the national level, #WFH for me was clearly rocking!

The crowning glory of the lockdown however has clearly been the haircut. Armed with a pair of small scissors, my daughter decided it was time. Had she messed it up beyond salvage, or chopped an ear off in the process, the experience would have been totally worth it. As it turned out, she managed a super job. And those badminton rounds in the late evenings, utter bliss. And baking the three-milk cake together, which from my heart and through my stomach has now taken permanent residence around my waist. Why would I exchange this for ‘normalcy’?

We have been blessed with a comfortable home, a spacious backyard where my wife and I make figures of 8 while walking vigorously each evening, and the peace of mind of a salaried income. And we are by the Grace of God, all healthy. We have not had to make difficult decisions, worry about pay cuts (yet) and having to worry about laying off our own staff, who have no other income source, no reserves of any kind. We are fortunate. And we are a minority. I make this entry in my diary fully aware of the plight of the vast majority, with more than a pang of guilt.

What? We have run out of ata (flour) again? Clearly, I have always been a closet homemaker all my life. Only, nobody knew it.

The fig tree that a colleague donated, liberated from a stunted life trapped in a pot in her driveway and moved to my lush forest last year, produces a baby fig. Excitedly, I break this news to my family, but the “duh” expression on my daughter’s face says it all. What’s the big deal, Abba? Let me know when the fig tree grows pineapples!

My fear about #WFH has been that it will end. As it should.

* Aamir Jafarey, Professor, Centre of Biomedical Ethics and Culture, SIUT, Karachi, Pakistan